The Bias in Consensus Conferences: A Critical Analysis

- Andre Chen

- Mar 20, 2025

- 3 min read

In recent discussions surrounding the field of dentistry, particularly related to ceramic implants, the topic of consensus conferences has emerged as a focal point of contention. While attending a meeting in Stuttgart, a very nice one indeed, i had the chance of running 13 km in surroundings with a glorious day. I found myself reflecting on the implications of these conferences and the systematic reviews that accompany them. Despite the beauty of the surroundings, the dialogue was overshadowed by concerns about the inherent biases present in these scholarly gatherings.

Consensus conferences are often perceived as a necessary means of advancing knowledge and practice. However, the manner in which these conferences are organized raises questions about their impartiality. It appears that financial backing from companies can significantly sway the outcomes, as prominent universities are invited to participate, often prioritizing their reputations over unbiased scientific discourse. When financial interests dictate the agenda, the validity of the conclusions drawn comes into question.

In the past five years, as noted in prior discussions, there have been approximately five systematic reviews and two consensus conferences focusing on ceramic implants. This raises a pertinent inquiry: why is there a need for such a multitude of evaluations? The redundancy of systematic reviews, particularly when they appear to echo similar findings, suggests a potential gap in genuine scientific inquiry.

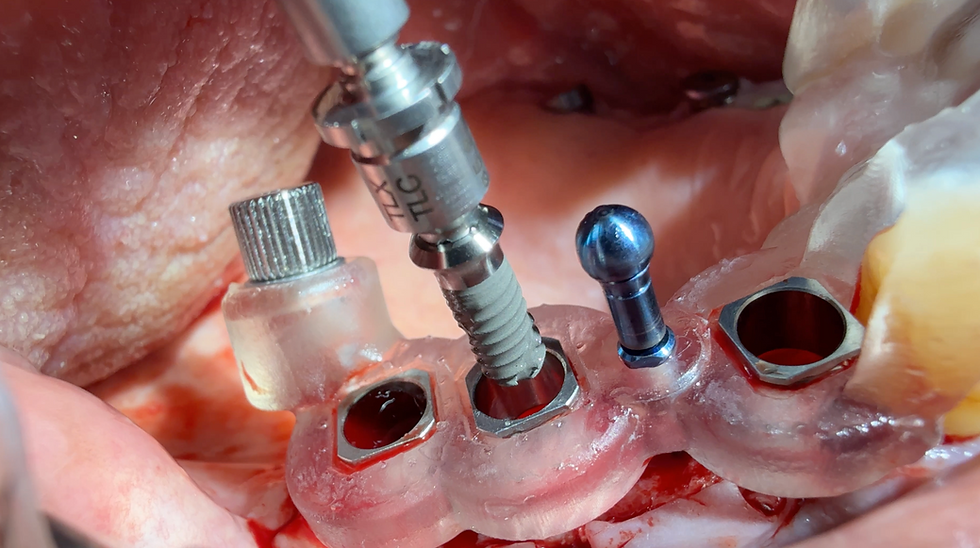

Critically, one must consider the qualifications of those producing these reviews. University professors may conduct studies with limited sample sizes—such as the evaluation of merely fifteen implants—yet derive conclusions that are positioned as definitive. In contrast, a practicing doctor, who has placed thousands of implants, possesses invaluable clinical insight that cannot be replicated in a controlled study. This disparity highlights the challenge of reconciling evidence-based practices with real-world experiences that practitioners encounter daily.

My criticism is that universities are supposed to teach students, and students graduate to become doctors who will treat patients. A teacher has experience in teaching students, while doctors treat patients; they are in the field.

Once I opened a ceramic implant paper, they discussed the outcomes of a two-piece ceramic implant in the market. The articles are indeed very good, but when considering the number of implants they evaluated, it was approximately 60 implants, and they drew conclusions based on those 60 implants. Now, how can this be deemed superior to the insights of a doctor who treats 6,000 implants and possesses a clinical intuition that is distinct from that of this professor at the university who conducted this limited study? I believe there is a bias present. If you wish to seek a fair opinion, if it is your life or your tooth that is at risk, it is evident that one of us would consult the doctor who places implants rather than rely solely on a paper discussing 60 implants.

What occurs nowadays is that we tend to rely more on, or at least give much more credit to, the individual who published this article because it is considered an evidence-based approach. We exist in an evidence-based world, and I regret to state that we inhabit a realm of political and money-driven dentistry, where the truth may not be as profitable as the "twisted truth".

The reliance on published papers often overshadows the clinical expertise of seasoned practitioners. As the field of dentistry evolves, it is crucial that we do not lose sight of the practical knowledge that comes from years of direct patient interaction. Evidence-based approaches are indispensable, yet they must be balanced with the realities faced in clinical settings.

Moreover, the overarching influence of financial motivations within dentistry cannot be overlooked. It is imperative that we question whether the current methodologies are genuinely producing beneficial science for patients, or if they are merely perpetuating a cycle of self-interest among those involved in consensus conferences.

In conclusion, as we navigate the complexities of dental science and its applications, it is essential to critically assess the structures that influence our understanding. The interplay of financial interests, academic prestige, and clinical expertise must be addressed to foster a more equitable and effective dental practice. We owe it to our patients and the integrity of our field to ensure that the science we produce is not only correct but also applicable in real-world scenarios.

Disclosure: This is a personal opinion not representing in any form ESCI position on this matter.

Comments