The art of rehabilitating the posterior maxilla/mandible

- Andre Chen

- Aug 2, 2025

- 3 min read

When I was at NYU, my dear friend João Sousa once asked me what my goal was in the program I had just enrolled in. I simply replied: “For me, placing implants in the posterior maxilla is the goal.”

Why? Because it fascinated me — the technical skill required, the anatomical challenges, the nerve proximity, the lack of space, the poor visibility, the ever-present saliva. And eventually… I managed to do it.

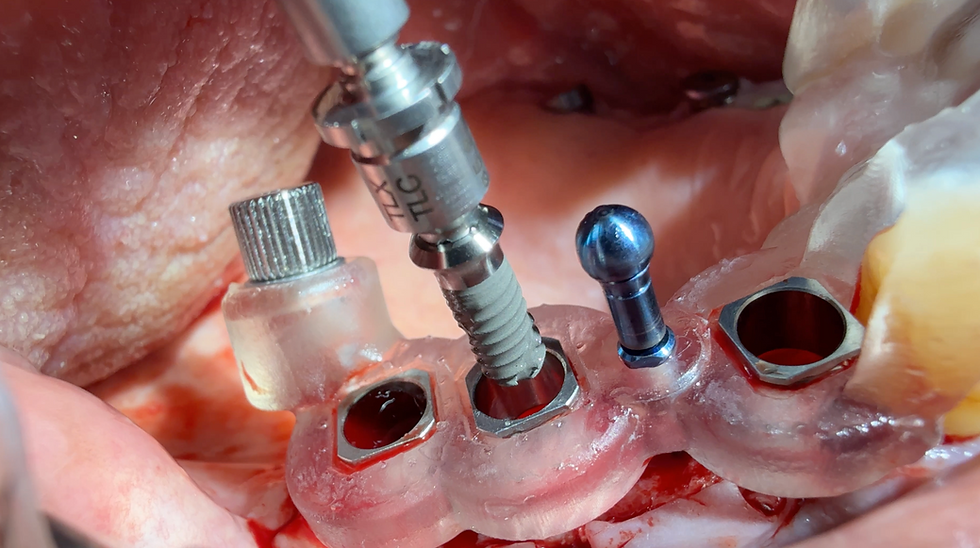

Even today, 4 mm implants used for posterior rehabilitation in cases of severe atrophy still fascinate me. This particular case represented the true limit of what technology can offer — both upper and lower arches.

I’m a big fan of sinus elevation, but the beauty of this case is that in just three months the rehabilitation was complete, and the patient was fully functional — without entering the sinus. No lateral window, no osteotomes, no osseodensification.

On the upper arch, we could argue about the challenge of type IV bone. Out of the 12 short implants I placed, only one showed a primary stability above 65 ISQ. The rest were all below 50.

And yet — here’s the surprising part — one year post-loading, all of them measured above 70 ISQ.

In the lower arch, the issue is always keratinized tissue. Haters and newly graduated clinicians will say you must have it for long-term health, protection, and implant survival.

I say: Yes, I would always prefer keratinized tissue.

But after all these years, what I’ve observed is that biomaterial selection, apico-coronal positioning, and lab technician skills are also critical — and can deliver stable results, even in the absence of keratinized mucosa.

I’ve seen this consistently using a supracrestal approach, with machined or polished collars on tissue-level implants, and also with zirconia dioxide implants placed supracrestally.

Many patients do just fine — no pain, no altered sensitivity, and extremely stable marginal bone over the years.

So before jumping into complex soft tissue augmentations for every patient, ask yourself: Does this case really need it?

In my practice, soft tissue augmentation is rare. I do some GBR for horizontal volume, but the majority of my cases rely on supracrestal implant placement — mostly titanium, and some ceramic. (And yes — a 6 mm ceramic implant is needed!)

As for implant diameter and friendship — they matter.

8 mm is better than 6 mm.

6 mm is better than 4 mm.

When you go to 4 mm, you’re already operating at the limit.

But don’t forget: 5.5 mm, 5.4 mm — these diameters provide significant surface area for osseointegration. In fact, a 5.5 x 6 mm may outperform a 3.75 x 8 mm implant when it comes to stability.

And please — spare me the Ante’s Law comparisons. I remember Dennis Tarnow, during our literature review sessions at NYU, used to say: “Well… it’s not really a law — it’s more like an awareness, a guideline, a recommendation.”

Ante’s Law applies to teeth and periodontal ligament support in fixed prosthodontics — not to osseointegrated implants, which behave completely differently in terms of load distribution and biomechanics.

And “friendship”? Yes — splinting implants matters.

One implant alone is always less stable than two splinted together, and three is even better than two. When implants are splinted, the osseointegration surface is shared, and they protect each other.

Finally, you can’t talk about posterior rehabilitation without considering the occlusal system.

You’re not just placing implants — you’re rehabilitating function.

If the case is overloaded, if there are interferences, you risk losing implants to occlusal trauma.

Work closely with your lab technician — make sure the curve of Spee, curve of Wilson, and the opposing arch are respected to ensure a balanced and distributed occlusion.

If the components are well-fitted and the occlusion controlled, then long-term success is mostly a matter of maintenance — both at home and in the office.

And don’t forget: once a year, check those occlusal contacts. Prevention is everything.

And finally — just remember: what if it were your mouth?

Which technique would you choose?

Would you really be willing to go through such demanding, technique-sensitive surgeries… if there were simpler, equally predictable alternatives?

Comments