Beyond the Guide: Real-Life Challenges in Full-Arch Surgery

- Andre Chen

- Jan 24

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 25

“Today we went for another surgery using Straumann’s new iGuide guided surgery system.

It was a full-arch case. An FP1, as many people like to call it, in reference to the book published by Karl Misch a few years ago. I think it’s a classification that has been very well revived for modern dentistry — a technique whose execution is naturally associated with the patient’s initial conditions.

A friend of Liliana, who fits perfectly into that indication — but only, of course, after an exhaustive prosthetic work-up and a refined planning process.

One of those cases that we planned with care, with detail, with everything prepared.

We had an extremely complex PMMA provisional — and that alone will already be a blog post.

The work behind a provisional like this is enormous… and here a special highlight to Sofia, our digital genius.

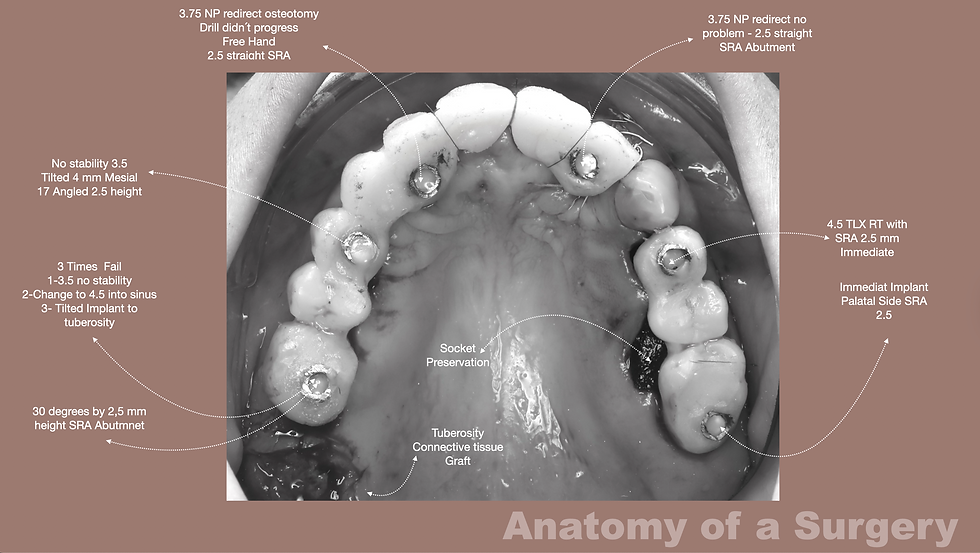

In surgery, the guide had six implants, metallic sleeves with a square arc design, 3D printed.

We took the guide to the autoclave… and it developed some cracks.

I don’t believe it had a direct influence, but it is an important point: cold sterilization might be a better idea for this type of material.

We fixed everything with three pins:

two palatal iGuide fixation pins

and one posterior pin, almost at the level of the tuberosity in the second quadrant

The initial adaptation was perfect.

The drill fit was spectacular.

Up to this point… everything was fine.

Palatal surgical approach illustrating flap design options: full-thickness, partial-thickness, and flapless zones.

Post-extraction sockets in the premolar and molar regions prepared for tissue-level implant placement.

Intraoperative view of the Straumann iGuide system with square sleeves and inspection windows for control.

Rotation markers and canine support features ensure accurate positioning and guide stability.

Anchor pin fixation and keratinized tissue management optimize access, precision, and soft-tissue preservation.

Since it was already planned to do an open surgery — which turned out to be the best option given the contrarieties that followed — I then decided to raise a flap:

full-thickness flap in the second quadrant

partial-thickness flap in the anterior region

because we were going to harvest a connective tissue graft from the tuberosity to gain volume, especially between tooth 11 and 12.

And this is where the setbacks begin.

When I repositioned the guide, even though the pins were correct, I started noticing a problem:

the fixation pins have a threaded ring — a great idea, I liked it, it increases stability.

But the sleeves for implant bed preparation require an absolutely perfect angulation.

If you don’t enter exactly on axis…

the drill gets stuck in the sleeve, it doesn’t go down, it doesn’t progress.

I started with the 26.

I performed the osteotomy… I felt there might be a lack of primary stability.

I thought it was just sensitivity, so I continued.

I decided to do an additional drill — 2.8 for a 3.5 implant.

And that’s where the adventure begins…

the Ride of the Valkyries.

The implant was literally floating.

Saying simply “no stability” would be an understatement.

That was a clinical flotation that deserves poetry.

At the 24, exactly the same thing happened.

Terrible bone.

Two implants that, if they had been placed “by hand,” as nuestros hermanos say, I would have felt it immediately.

But I didn’t.

I had to compensate with the “bazooka”:

TLX 4.5 x 12 mm — a masterpiece of primary stability.

Tulip collar, wedge effect at the crest…

and voilà: torque of 50.

Then, at the 22 and the 12, another problem arose:

the iGuide drill simply would not descend into the sleeve.

And when it did descend, another issue appeared: since I had not done a punch in the palatal tissue, it could not progress.

Because these drills have a non-active barrel shape — and an active tip — and the drill only cuts at the tip.

I had to stop.

I removed everything, did a punch, cleaned the keratinized tissue that was blocking the seating.

And at that moment I realized:

I didn’t have the conditions to continue with the iGuide.

Either I treated the patient…

or I treated my ego.

I chose the patient.

I removed the guide… and switched to freehand for the 12 and the 22, always with absolute control of the emergence.

In the first quadrant, I decided to keep the canine — because of the canine eminence — and it was an excellent aesthetic decision.

I extracted 14, 15, 16, and 17.

I placed two immediate implants:

at the 14 with good stability, TLX again because of the tulip collar

at the 17 with very poor stability, ISQ 50 — increased risk

I anchored the 17 on the palatal side, slightly distal, which compromised the position a little…

but still within the rehabilitation envelope.

Since the final position had moved away from the original planning, we did not use the second prosthetic guide.

At the 26, I opted for an angulated TLX tissue-level implant, 4.5 x 12, tulip design.

I achieved a good emergence with a 30° angled abutment.

At the 24, I re-angulated mesially…

and then yes: ISQ 76.

The 4 x 12 engaged well.

Sofia did an incredible job with the provisional.

We divided it into two structures:

12 to 26

and a short bridge from 14 to 17

We lost some stability by no longer having the splinting effect of a full arch, greatly reducing the anterior-posterior spread, but we gained aesthetics by keeping the canine.

Capture, polishing… and I finalized the connective tissue graft from the tuberosity:

internal suturing with Vicryl 5-0

closure with Gore-Tex by primary intention

and nylon sutures for coronal repositioning

In the end:

provisional screwed in

occlusal adjustment

control CBCT

case completed

Now… I will be honest:

it was not a perfect case.

We had problems with the iGuide, difficulties with primary stability, and we ended up performing a large part of the protocol freehand.

It was disappointing because we expected a different behavior from the guide.

But it was an enormous learning experience.

And it also left us with very clear take-home messages.

After working with iGuide in a demanding FP1 scenario, here are five mistakes to avoid:

1) Autoclaving the surgical guide without validating the material

3D-printed guides may develop microcracks or thermal distortion. Even small deformation can affect passive seating and sleeve tolerance.

➡️ Cold sterilization may be the safest option.

2) Trusting the initial fit before flap elevation

A guide may seat perfectly at first, but after flap manipulation, repositioning is never identical.

➡️ Always reconfirm passive fit and drilling axis.

3) Underestimating the critical angulation required by metallic sleeves

iGuide sleeves require perfect coaxial entry. Any deviation can cause the drill to bind.

➡️ Never force the drill — stop and reassess.

4) Skipping tissue punch or soft tissue clearance in palatal areas

Non-cutting barrel drills cannot progress if tissue blocks full sleeve engagement.

➡️ Perform punch and clear access before osteotomy.

5) Persisting with the guide when primary stability does not match real bone conditions

A guide provides position, but not tactile feedback.

➡️ If stability is compromised, adapt, change implant strategy, or convert to controlled freehand.

The goal is to treat the patient, not to protect the ego.

And the final message is simple:

Guided surgery is a tool — clinical judgment remains the true navigation system.

And for the next one…

We will be much more prepared…..

Have a nice January !!!

Comments